Dissecting the HMC 4.5 system for fun (and profit?)

If you’ve read this blog before, you might already know that I like IBM systems, as they are weird and somewhat exotic compared to other manufacturers’. IBM’s hardware is also solid and seems to last a long while, but it has a major problem: the systems don’t like me… or you. They don’t even like the people who actually shelled out thousands of dollars to buy or rent them when they were new.

Today’s story revolves around the Hardware Management Console (HMC), a piece of software that runs on an x86 machine (not any machine though, more on that later) and is supposed to be used to configure POWER systems remotely. “Sort of a web UI for convenience”, you might say… and you’d be wrong. Apparently the HMC is mandatory to perform operations such as LPAR management and resource management in general, things you cannot do from either the Service Processor’s firmware or the System Management Services (SMS) boot menu that is still present in CHRP POWER systems.

Arguably, the HMC is very useful in a datacenter, as you’ll be able to manage a fleet of machines from a single centralized interface – the only downside is that if you only have a single machine and no HMC hardware, you’re basically screwed: IBM never sold the HMC as a software product, but rather as a bundle. You bought an HMC license and you got an x86 machine with a special BIOS that ran the HMC software.

This article will explore version 4.5 of the HMC software, an early one, and we’ll dive into the verification process to see if we can fool it and get the system to run in a VM.

HMC 4.5

The HMC is a Linux-based system which boots to a customized environment and launches a Java applet that can be used to manage POWER systems. HMC 4.5 comes on four CD-ROMs and is uses PowerQuest EasyRestore 5.0 to copy it back onto the hard drive.

The first CD is bootable and contains EasyRestore and the disk image, while the other CDs contain RPM packages that will be installed directly by the Linux system later on.

Hardware Requirements

HMC runs on regular IBM hardware with a customized BIOS. The only difference between a regular BIOS and an HMC BIOS should be minimal and mainly confined to the DMI strings determining the machine’s model.

HMC 4.5 supports the following systems:

| Model VPD | Model | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6578 | NetVista 6578 | Desktop | Regular BIOS |

| 6579 | NetVista 6579 | Desktop | Regular BIOS |

| 6792 | NetVista 6792 | Desktop | Regular BIOS |

| 7032-M04 | Unknown | Unknown | Has a touchscreen |

| 7315-C01 | NetVista M41 (Black) | Desktop | Uses 6792 tarball |

| 7310-C03 | ThinkCentre M50 | Desktop | |

| 7310-C04 | ThinkCentre M51 | Desktop | |

| 7310-CR2 | xSeries 335 | Rackmount | |

| 7310-CR3 | xSeries 336 | Rackmount | |

| 7315-C02 | Unknown | Desktop | |

| 7315-C03 | Unknown | Desktop | |

| 7315-C04 | Unknown | Desktop | |

| 7315-CR2 | Unknown | Rackmount | |

| 7315-CR3 | Unknown | Rackmount | |

| 7315-R01 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 7310-C02 | Unknown | Desktop |

According to this document the NetVistas don’t support V4, but the files on the disk seem to suggest otherwise.

Installing on VirtualBox

As the HMC is basically a heavily modified Linux distro (I believe it’s based on SuSE), we should be able to install it in a VM or on any other x86 system… that is, unless the software actually restricts us from installing it on a virtual machine; let’s see how we can work around that.

Setting up the VM

Let’s start by creating a VirtualBox VM as follows:

- Type: Linux

- Version: Linux 2.4 (32-bit)

- Memory: 1024 MB

- HDD Size: 40 GB (IDE PIIX4)

- Pointing Device: PS/2 Mouse

- NIC: AMD PCNet-III FAST

The installation is unremarkable, but you should make sure you have a disk that’s bigger than 40 gigabytes, as EasyRestore will barf if the disk is too small. I’ve also found that using bigger disks will make the restore process unbearably long and, in some cases, will make it hang altogether.

Spoofing the BIOS strings

Those who came before suggested changing the System Product and System Vendor DMI strings to fool the HMC software, making it believe it’s running on real hardware. Further research seems to indicate that the System Vendor string is not part of the verification process, at least on HMC 4.5, which checks the BIOS Vendor string instead.

The following commands allow us to trick the HMC software into believing that it’s running on a legit machine by modifying the DMI information VirtualBox presents the VM with.

$ VBoxManage list vms

"IBM HMC 4.5" {73cd5db6-71d5-4f59-9787-e8d5613b5454}

$ export VM_UUID=73cd5db6-71d5-4f59-9787-e8d5613b5454

$ VBoxManage setextradata $VM_UUID "VBoxInternal/Devices/pcbios/0/Config/DmiSystemProduct" "7310CR2"

$ VBoxManage setextradata $VM_UUID "VBoxInternal/Devices/pcbios/0/Config/DmiBIOSVendor" "IBM CORPORATION"

The VirtualBox docs have a list of all the DMI strings you can mess with.

Setting back the date

Once you’ve restored the OS to the hard drive, the system will reboot into Linux, and it will prompt you for disks 2, 3, and 4. The installation process checks each CDs’ signature: the verification fails if the machine’s clock is set to today’s date (due to certificates being expired, I think). VirtualBox allows us to set back the BIOS clock to fool the VM into thinking that it’s still 2004.

$ VBoxManage modifyvm $VM_UUID --biossystemtimeoffset -631139040000

This method allows us to proceed with the installation and get to the login screen.

When prompted to “Restore critical console data from DVD media” you should choose 2 to finish the installation;

Post-install

Once the last CD has been processed, the system will reboot and X11 will fail to start. Login with hscroot/abc123 then su - with passw0rd (you cannot login as root by design). This is a good thing because the X11 environment is completely sandboxed and, once it starts successfully, console logins will be prohibited. If this wasn’t the case, we’d probably have to access the disk using a Live CD, mount the partitions and modify the files.

While we’re here, we’ll do the following:

- Mess with

inittabto always give us a login prompt - Fix the X11 config

- Spoof the Restricted Terminal

You can also enable SSH as explained by this guide.

Accessing using a Live CD

I’ve managed to explore and modify the files on the disk using an Ubuntu Linux live CD. I went with the first release of Ubuntu, 4.10, which uses Kernel 2.6.7. I discovered that hda5 is / and hda6 is /usr.

Login Prompt

To always get a login prompt, we’ll add a new virtual terminal in inittab. The HMC setup process cheekily disables all getty processes so you can’t log in from either the virual console or the serial console once the X11 session starts up. To work around that, we add the following line at row 73 of inittab:

3:2345:respawn:/sbin/mingetty tty3

This will make sure we can always login from VT#3 (VT#1 is the boot console and VT#2 is the X11 session). I also modified the kbrequest line to execute /sbin/shutdown 0, so in case of emergency we can press Alt+↑ to get into single user mode.

X11 Fixes

To generate a valid X11 configuration, do the following:

# /usr/X11/bin/./X -configure

# mv /etc/X11/XF86Config /etc/X11/XF86Config.old

# mv /root/XF86Config.new /etc/X11/XF86Config

# exit

$ startx

You should get a familiar X11 session with dwm and the checkered background. You can also play around with the X11 config to try and get a higher resolution desktop, but I haven’t had much success in that regard.

Spoofing the Restricted Terminal

The HMC gives you a Restricted Terminal called rshterm in an attempt to sandbox you into the HMC environment. This terminal disallows executing any command that contains a / in its name, and has a whitelist of allowed commands. In theory, we could add an entry to the Fluxbox menu configuration (/opt/hsc/data/fluxbox/menu) but this seems to be ineffective for some reason. To work around this, I’ve replaced the launchrshterm executable with a symlink to xterm:

# cd /opt/hsc/bin

# mv launchrshterm launchrshterm.old

# ln -s /usr/X11/bin/xterm launchrshterm

This will launch a regular xterm instance instead of the restricted shell. If you need rshterm you can run launchrshterm.old from xterm.

Setting up sudo

This is not required, but apparently the system has sudo installed. We can edit /etc/sudoers to let hscroot use sudo:

# groups hscroot

hmc root

# visudo

Add the following line:

%hmc ALL=(ALL) ALL

:wq and reboot.

The VPD conondrum

Vital Product Data (VPD) is IBM parlance for “a bunch of magic numbers that identify the hardware”. As we already mentioned, the HMC checks for VPD in the form of the “System Product” and “System Vendor” DMI fields: if the strings don’t match, you won’t be allowed to use the HMC software. This is a common technique IBM used to charge more for the same products on the premise that they’re allowed to run specific software, which is usually leased to the end user with a restrictive license that only allows them to use it on a specific machine, possibly for a limited time.

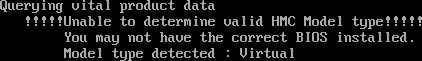

If we want to run the HMC on a regular computer (e.g. a ThinkPad laptop), we need to override the VPD check. This turned out to be incorrect, at least on HMC 4.5; after careful consideration I gathered that:

- Neither the installation/restore process (CD #1) nor the installation of packages (CDs #2, #3 and #4) check the VPD, meaning you can install HMC 4.5 pretty much on anything you want.

-

On the first proper boot,

hmcConfigwill run for the first time and complain about the BIOS: this does not result in a boot loop! It will simply warn you that your BIOS is wrong and go on with its business. This, however, will mean that you’ll have to runX -configuremanually and copy the resulting XF86Config.

- If you change the System Product DMI entry after the system has been successfully configured, nothing seems to happen: this is because the VPD verification portion of the

hmcConfigscript will create thehmcConfiguredfile once it has completed successfully. This also means that a simpletouch /opt/hsc/data/hmcConfiguredwill effectively prevent the VPD check from happening altogether.

The VPD decoding process

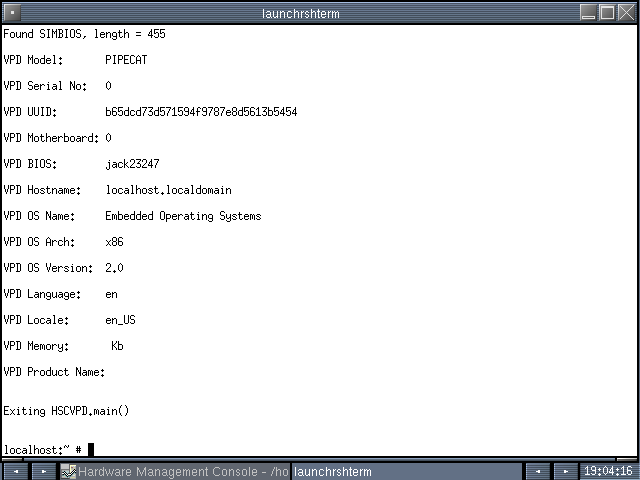

On HMC 4.5, dmidecode does not exist yet: the check is performed by a script (/opt/hsc/bin/getHMCVPD) which wraps around a Java class (com.ibm.hsc.common.util.HSCVPD, part of /usr/websm/codebase/pluginjars/hsc.jar) that decodes the VPD information and returns a specific string.

If you run the Java class without the wrapper (as root, or it will barf), you’ll get the following:

The wrapper (getHMCVPD) appropriately greps and cutss the output of the Java program and supports the following options:

| Option | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| None | Returns the Model/Type string | 7310CR2 |

-a |

Returns a Model/Type string, followed by a * and the Serial Number |

7310CR2*0 |

-b |

Returns the BIOS string | |

-g |

Returns the VPD’s UUID |

It would be easy to modify this script to always return

7310CR2in lieu of the Model, but I suspect that the UUID is used in a verification step somewhere.

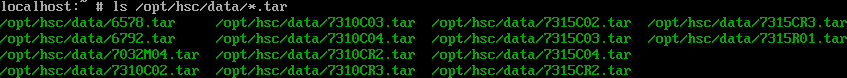

getHMCVPD is called by an init script (/etc/init.d/hmcConfig) that tries to infer the HMC’s model and match it against a “database” (i.e. a bunch of tarballs) found in /opt/hsc/data; the archives contain appropriate configuration files for each model supported by IBM. The verification/configuration portion of the init script runs only if the /opt/hsc/data/hmcConfigured file does not exist.

By looking at this script and the tarballs, it seems like the black desktop NetVista (6792) and the white desktop NetVistas (6578 and 6579) are supported even with their regular desktop BIOS.

The following picture shows all of the tarballs present on the disk image; they are quite simple, and essentially contain an appropriate X86Config for each machine.

Based on this information I speculate that:

- Adding support for the regular BIOS counterparts of the supported systems is a matter of adding a copy of the tarball with a different name;

- Adding VirtualBox, VMWare and qemu support is possible by adding appropriately named tarballs containing appropriate configuration files;

- Adding support for other systems is possible as long as you add a baseline config and modify

/etc/init.d/hmcConfigto apply that and warn the user instead of exiting forcefully.

Further Research

What does com.ibm.hsc.common.util.HSCVPD do?

To answer this question, I extracted the .jar file from the disk image and explored its contents using an online Java decompiler and I discovered the following:

- The program basically reads straight from

/dev/memat appropriate locations, determining if the system has a System Management BIOS (SMBIOS):- If the SMBIOS is present, it’s used to determine the System’s Model and Type;

- If it’s absent, the program retrieves the VPD table from memory and decodes it.

-

The package contains a list of approved “System Names” in a

.propertiesfile, which basically maps a model number to a readable name:$ head -n 5 IBMNames.properties [System Names] 6260-??? = IBM PC 140 6268-??? = IBM PC 300GL 6272-??? = IBM PC 300GL 6278-??? = IBM PC 300GLThe

getHSCProductName()function extracts the model number from the VPD and essentially gives up and returns an empty string if it can’t match it with an entry in the.propertiesfile.This file seems to be missing several important entries, such as xSeries servers: this is probably intentional, as newer systems with an SMBIOS should have a dedicated entry. If we trust the output of the disassembler, however, the function seems to contain a bug: if an SMBIOS is detected, the Product Name is extracted, but then the function doesn’t return the value and tries to match the (non-existent, I imagine) VPD data with the

.propertiesfile and returns that instead.

If you want to play around with the

.jarfile, just send me an email; getting files out of the VM was quite painful. I ended up using the Ubuntu Warty live desktop to copy the files to a secondary drive I added to the VM (1024MB, raw disk image) and formatted as FAT32; the disk image was then mounted on the host. FTP would have worked just as well if I had access to a server and a real network.