Today I Learned… about Windows CE!

I’ve been wondering about the internals of Windows CE today and I learned that the Kernel of CE 6.0 has been released under a semi-open source, with a “shared source” model. This is a great opportunity to learn how an independently designed OS works internally.

What is Windows CE?

Windows CE is a largely forgotten effort by Microsoft to produce a small, portable and Real-Time OS that supported a subset of the Win32 API. Windows CE’s first release came all the way back in 1996, while the last release is CE 8.0 from 2013.

CE, which (allegedly) stands for Compact Embedded, supported several architectures that were popular with small and embedded devices at the time. The initial release of CE ran on MIPS and Hitachi SH CPUs, and it later gained support for ARM1, x86 and PowerPC processors. By the time version 7.0 was released, in 2011, the kernel supported only x86 and ARMv7, while retaining limited support for Hitachi SH chips in automotive scenarios.

The GUI was a pivotal part of CE, which ran a cut-down version of the familiar Windows Desktop. This platform was immensely popular for a time, and powered platforms like PDAs, infotainment systems, and kiosks2. A number of applications were developed for the platform, including version of the Office suite, games like Age of Empires and countless other touch-oriented productivity apps.

Windows CE’s last gasp was version 8.0, released in 2013, for which extended support will end this October.

The WinCE Core Team Blog

I’ve stumbled across this information while reading the Wikipedia article about WinCE in an attempt to understand whether or not it used a microkernel: from there, the citations led me to the very interesting WinCE Core Team blog, that’s still readable thanks to the Wayback Machine. Here’s the most interesting articles I’ve found:

- How does Windows Embedded CE 6.0 start? – Deep dive into how the Kernel is structured and how it’s loaded into memory. The author somewhat demistifies the Kernel code and gives a clear explanation of its structure and of the boot process.

- Real-Time and Threads – An article where the author does some Q&A regarding the Hard Real-Time nature of the OS and how the interrupts are serviced (with a fast, non preemptible ISR and a threaded handler, which is similar to how Linux does it). Moreover, she directs the reader to the sources, and that’s how I learned about the shared source model.

Getting the sources

The sources, according to this article were available on the official SDK DVD and directly from MSDN. While it’s probably impossible to get them from the latter now, the SDK has been Archived and is available for download:

A cursory look at the Release Notes found on the DVD image confirms that the sources should be available once the SDK has been installed from the first DVD.

Installing the SDK

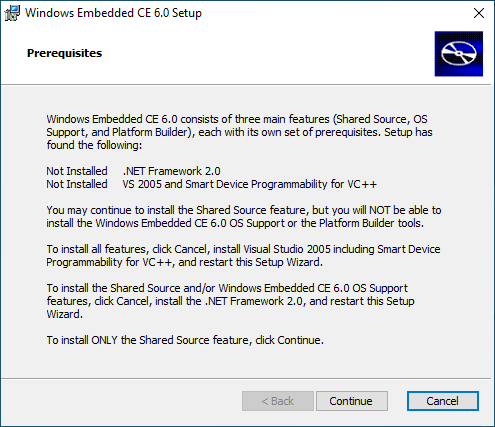

I downloaded the DVD and tried to run it on a Windows 10 VM on a whim. The installer barfed because it could find neither .NET 2.0 nor Visual Studio 2005 with the proper component installed.

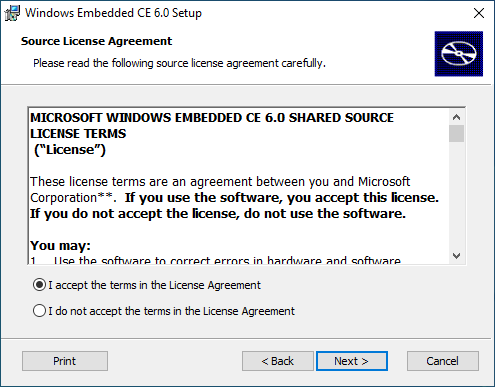

Luckily, whoever built the MSI allowed for installing “ONLY the Shared Source feature”, so I pressed on. After inserting the product key and selecting the Shared Source component for installation, I was presented with the license agreement for the Sources.

I only gave it a brief glance but I can tell you that this is not an OSI approved license, and it seems to me like it’s essentially meant for OEMs to develop and market their own OS extensions.

After accepting the Agreement, the installation proceeded and I was left with the source tree placed in C:\WINCE600. I have compressed the folder and uploaded it to Archive.org, so you don’t have to spin up a Windows VM if you want to look at them.

The source tree

The source tree contains several components, only one of which is the OS itself.

[WINCE600/PRIVATE]$ tree -d -L 1

.

├── DIRECTX

├── OSTEST

├── SERVERS

├── SHELL

├── TEST

├── WCEAPPSFE

├── WCESHELLFE

└── WINCEOS

I am not interested in analyzing the whole source tree for now, and I will focus on what’s inside WINCE600/PRIVATE/WINCEOS/COREOS.

[WINCE600/PRIVATE/WINCEOS]$ tree -d -L 1 . -R COREOS

.

├── COMM

├── COREOS

├── DRIVERS

├── INC

└── UTILS

COREOS

├── CEPTR

├── CORE

├── DEVICE

├── FSD

├── GWE

├── INC

├── NK

├── SHELL

├── STORAGE

└── TOOLHELP

The kernel code is stored in COREOS/NK, and the core library is in COREOS/CORE. I’ve taken a quick glance at the NK code, but I feel like I need to gain some additional knowledge on the general design and the internals of the Kernel before diving deep into it.

Wrapping up

Having an “official” way to look at the WinCE source code is really exciting, and the whole endeavor led me down a quite deep rabbit hole. Out of curiosity, I located a copy of Inside Microsoft Windows CE by John Murray (which will probably be featured on an issue of Quarterly Book Review once I’ve read it) and I hope to have some free time this summer to look at the sources properly and document what I find most interesting.