Core Transfer

“To initiate a core transfer, please deposit substitute core in receptacle.”

The AS/400 is a weird platform: it’s unique, full of quirks, and its software stack is so well integrated with the hardware platform that the machine can order spare parts automatically from IBM. The quirky nature of the AS/400, along with a reasonable entry barrier, makes it a very interesting platform for the masochist hobbyist like me who’s interested in old and somewhat obscure systems.

The problem

However, the tight integration comes at a cost: for starters, if you need spare parts you’re gonna have a bad time, since even the disks are proprietary (despite being bog-standard SCSI they use custom sector sizes and are firmware locked). Moreover, the licensing scheme is incredibly convoluted (very business-oriented, if you know what I mean), and it’s terrible for hobbyists: if you don’t have the licenses for your system, you’re bound to reinstall everything every 70 days.

The older machines (CISC ones) go even further: every CPU card has something called Vital Product Data (VPD), a bunch of numbers that is unique to that card and factory paired to the front panel. This means that the pairing information is stored on both battery-backed RAM and on the disk: both things go bad at the same time you lose the pairing info and end up with a very heavy door stopper. Newer machines are somewhat more relaxed, but if you lose your LICKEYs you’re bound to the 70 days cycle anyway.

2020-03-19:jack23247 Ok, so, I got the whole VPD thing incorrect: it’s way more complicated than that and not limited to CISC hardware, so even, say, a 270 or a POWER4 iSeries might get nuked (I still don’t get the full picture so don’t quote me on this). Also, later machines (POWER3+ probably) have a dedicated bootstrap processor housed on a “VPD card” which kills the system if it goes bad.

Neat.

The Model 150

There is exactly one loophole in this whole licensing ordeal: the 9401-150. The 150 was the slowest machine of the AS/400e line, but also one of the most aggressively priced: IBM figured that to attract small offices and application developers they could entitle anyone who bought a 150 to run the whole V4 distribution on it without getting any additional license. For this reason, the 150 was extremely popular in europe (specifically in Italy, where they were assembled in the Santa Palomba plant) and there are a ton on the used market. Moreover they’re small, silent, electrically cheap to operate, and they weigh like a conventional tower PC: it’s a hobbyist’s dream machine for sure.

An unfortunate rescue

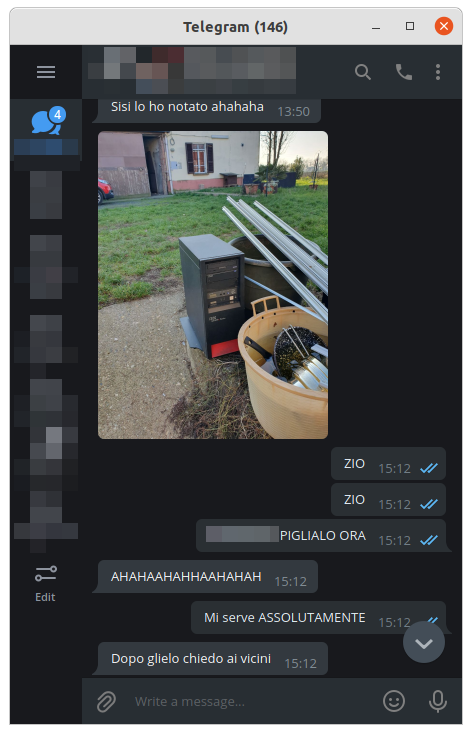

There are so many 150s here that you might literally come across one by chance, like I did with one of those I acquired. In December 2019, out of the blue, I got this message from a friend:

…and let’s just admit I was a bit too excited.

The system was pretty beat up, and it’d sat in light rain for a couple days (the water in the yellow bucket is rain) before my friend was able to formally acquire it from his neighbors. Sadly, it failed to IPL with an MFIOP error (which I might’ve nailed down to a broken capacitor leg on the backplane).

I think a little bit of vocabulary is due here:

- Direct Attached Storage Device (DASD) is IBMese for “disk drive”. So a single DASD is technically a disk drive, at least in the midrange world. I sometimes call DASD the whole disk array as that’s closer to the original meaning of the term.

- Attached Storage Pool (ASP) is a term that indicates how the OS “sees” (and partitions) a bunch of DASDs, think of it as an LVM or ZFS volume. An ASP can either be supported by an underlying RAID array (a RAID of DASD) or use the disks directly, just like LVM, and most of the time it encompasses a bunch of disks.

- The Initial Program Load (IPL) is the equivalent of a PC’s boot process. When powering the system on, the Multifunctional I/O Adapter’s (MFIOA) fancy SCSI controller scans through the attached DASD, searching for a Load Source (the place where the LIC resides).

- Licensed Internal Code (LIC) is an hybrid between a kernel, a BIOS, a set of recovery tools, and some kind of low-level virtual machine (similar to the JVM or M$’s CLR). Basically, even to perform the most basic task you need a working Load Source.

Being unable to make it progress further I was left wondering about what actually resided on the ASP, and whether or not it was still IPLable. Afraid to softlock my good machine by fiddling around too much, I’ve never attempted to recover the content of the platters, and the system basically sat there unused as a “spares only” unit.

Curiosity killed the cat…

After having a talk with the small yet incredibly talented group of AS/400 hobbyists on Discord, I’ve decided to try and swap in the DASD set (which I’ll refer to as “core” from now on) from the spares machine to the working one, to see if it would IPL. My concern was that the core from the working machine could be crippled as the MFIOA could mix the disks up and “forget” the load source: this later turned out to be wrong, since the ASP geometry is stored on the load source and the MFIOA has to look for it on each IPL anyway.

Since the system on my good machine is crippled and needs to be reinstalled anyway, I decided to give it a go and swap the cores.

Swapping the drive cage on the 150 is quite an uneventful process: the whole cage is held mechanically by two tabs that grab the 5.25” bays, and by a clever locking mechanism that uses a long screw to lodge a bracket into the tab that protrudes from the back of the drive cage (you can see it in the picture above on the back of the cage sitting atop the machine). While the drive cage comes off whole, it takes a considerable amount of force to dislodge it from the frame: in the (truly ritual) process, I managed to smash my fingers against the aluminum fins of the CPU heatsink, smearing it all with blood.

..but satisfaction brought it back

After cleaning and putting together the system, I flicked the switch on the PSU. Immediately, the front panel sprung to life, displaying 01 B N in bright green letters as if it was daring me to initiate an IPL.

Bis the IPL side,Nis the operating mode. Here’s a chart:

A B C D IPL the LIC’s Permanent Copy (no PTFs) IPL the current LIC and PTF set Hardware Service Representative reserved IPL (aka black magic from Castle Rochester, NY) Attempt to IPL from removable media You commonly IPL from side B, but if you’re not happy with the last set of Program Temporary Fixes (PTFs, aka patches) you applied to the system you may IPL A and apply a different set (kinda like recovery checkpoints in Windows). Side C is weird (hic sunt leones), and side D is used to perform system installation from removable media (CD-ROM or tape).

The operating modes quite straight forward:

Manual (M) Normal (N) Attended IPL, letting you interact with the

boot process before the subsystems are startedDirectly IPL to full system capacity,

it’s used normally in productionThe attended IPL is very useful to work with the system as, for example, it allows you to use the Dedicated Service Tool (DST), which is used to work with low-level system configuration.

I was hesitant: what if I messed up and killed my only working 150? “Screw it”, I thought, while hitting the big white square.

The cold start proceeded, albeit at a snail’s pace: the system was probably quite confused (or just needed to be dusted off since it was not IPLd since 2016). After grabbing a bite I came back and looked in awe at the system greeting me with SCSI drive noises and a login prompt. My excitement was (once again) hard to contain: the core can be swapped between 150s! This means that if one of those machines is missing its DASDs or your ASP is rendered unbootable by a failed platter, you can still rescue it by swapping in another known-working core.

I could (thankfully) login with the default QSECOFR (Security Officer aka root) password… which is QSECOFR (imagine if all Linux boxes had credentials root/root enabled by default) and play around a bit. It seems like the machine had been used as an RPG box to port an older application from a System/36 to the integrated SSP environment on OS/400, and it had a somewhat weird 192.168.0.1 IP.

Conclusions

And that’s it: I reverted the machine to its original configuration and was indeed able to IPL it without any hiccups, while being incredibly excited by the notion that I can swap a disk with another (identical) one without bricking my weird little machine. This is why I find the AS/400 so interesting: everything is different enough from any other computer system you’ve used for you not to be able to take anything for granted, but if you play around with them long enough you’ll eventually build some solid skills.